Private Equity 20 Lectures (7) CFIUS's past life

Previous issues we have talked about are the detailed concepts in private equity, but in addition to specific knowledge points, we also need to focus on the general environment of private equity investment, speaking of the general environment, we have to mention the CFIUS review of the United States.

I. CFIUS development of five stages

Most of me heard of CFIUS should be from Trump 20218 enacted the FIRRMA Act began, that time I also wrote an article on WeChat 10w+ is to explain the FIRRMA Act, but in fact, the United States foreign investment review system has a hundred-year history:

1. the gestation period of the system (World War I-1974). As early as during World War I, (U.S. President Woodrow Wilson) in order to prevent German investment in the U.S. military-related industries, in 1917 passed the Trading with the Enemy Act, so that the President was given the right to deal with the trade relations of enemy countries. But because by the end of the war, the United States needed an open-door policy to attract large amounts of foreign investment, there was no actual act or special executive agency to review foreign investment during this period.

2. The initial period of the system (1974-1988). In the 1970s, the U.S. economy entered a period of stagflation while OPEC countries were buying U.S. assets with "petrodollars". So in 1975, during the administration of President Gerald Rudolph Ford, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) was established, which marked the beginning of a real foreign investment review system in the United States. However, at this time CFIUS was just established, only to play a role of research and analysis, far from the level of actual restrictions on foreign investment.

3. the period of institutional formation (1988-2001). the influx of Japanese capital in the 1980s and 1990s led to the passage of a series of bills, including the Exon-Florio Amendment in 1988 (signed by U.S. President Ronald Reagan) and the Byrd Amendment in 1992 (passed by George H.W. Bush Sr. George H.W. Bush, Sr.) passed the Byrd Amendment. In this period, CFIUS "transformed", not only has the power of substantive review, but also can take coercive measures. At this point, the U.S. national security review system for foreign investment has basically taken shape.

4. The period of institutional improvement (2001-2017). After the terrorist events of September 11 in the new millennium, the U.S. government and people panicked, and national security issues became urgent. This is when the Dubai port merger case ignited the fuse and President George W. Bush Jr. signed the Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007 (FINSA). The authority of CFIUS swelled again, and the number of reviews rose dramatically. The U.S. foreign investment review system came of age during this period.

5. A period of heightened scrutiny (2018-present) This time it is the Chinese threat that worries the U.S. The Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA), passed by President Donald Trump in 2018, has "upgraded" CFIUS once again: the scope of control is wider, the manner of control is more detailed, and the person in charge There are more people in charge. By the first year or two of President Joe Biden's presidency, it was thought that Biden would weaken the Act, but it was not expected that the Act would be strengthened again after Biden issued Executive Order 14085 in September 2022.

From these five periods it can be seen that every time the United States feels that other countries pose a threat to him, it will strengthen the strength of the foreign investment review sub, the power of CFIUS will rise again.

II. the institutional composition of CFIUS

CFIUS is mainly led by the Department of the Treasury, its membership is divided into

1. 9 heads of voting departments (Secretary of the Treasury, Attorney General, Secretary of Homeland Security, Secretary of Commerce, Secretary of Defense, Secretary of Energy, Secretary of State, U.S. Trade Representative, and Director of the Office of National Science and Technology Policy);

2. the heads of the 2 non-voting departments (Secretary of Labor, Director of National Intelligence)

3. 5 heads of observer departments (White House Office of Management and Budget, President's Council of Economic Advisers, National Security Council, National Economic Council, Homeland Security and Counterterrorism Council).

III. Changes in the intensity of CFIUS review

1. Total number of reviews

CFIUS is also gradually strengthening its efforts in reviewing foreign investment cases.

Phase I: The period from 2005 to 2008, when the review was very weak, CFIUS only received a total of 468 review applications, only 37 of which were formally investigated, which accounted for only 7.9% of the total number of applications.

Phase II: The period from 2009 to 2016 saw a gradual increase in scrutiny, with CFIUS receiving a total of 938 applications for review and conducting formal investigations on 389 of them, which accounted for 41% of the total number of applications.

Phase III: The phase from 2017 to 2019, the review was further strengthened, CFIUS received a total of 697 review applications and conducted formal investigations on 443, the investigation accounted for 63% of the total number of applications.

2. Top 10 countries in terms of number of reviews

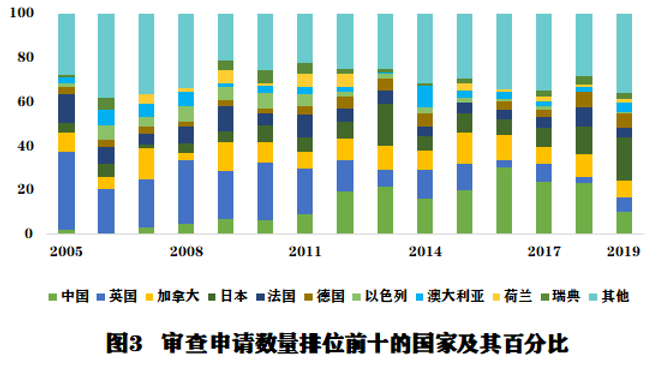

China's investment review applications to the U.S. have been increasing year by year, and you can just look at this green section which has been increasing year by year overall with each year. And always maintain the top ten, of which a few years can already be said to be the first place.

Fourth, the CFIUS review stage

CFIUS implementation of the review in stages.

1. the first stage "general review phase", a period of 30 days, if the project is considered doubtful to enter the second stage "special review phase";

2. the second phase "special review phase", a period of 45 days. A decision may be made directly or reported to the President, who may rule that a decision should be made within 15 days.

The U.S. has the strongest interest in reviewing Chinese investment transactions. Historically, there have been six cases in which the President has signed an executive order calling for a halt. Five of these cases involved Chinese companies directly and one involved a Singaporean company, but the reason for this call-off is also indirectly related to China.

1. In March 2012, Ralls Corp, a U.S. subsidiary of SANY, acquired four wind farm projects in Oregon, USA. On September 28, 2012, Obama issued a presidential order prohibiting Ralls from the Butter Creek wind farm project in Oregon. Trinity's wind farm investments in the U.S. were banned by CFIUS, but Trinity later sued President Obama, arguing that the ban it issued violated procedural justice. It was not until 2015 that Sany Group withdrew its lawsuit against President Obama and CFIUS, and the U.S. government accordingly withdrew its lawsuit to enforce the presidential order against Rolls, reaching a comprehensive settlement.

2. In 2016, Fujian Hongchip, the German arm of Fujian Hongxin Investment Fund, planned to acquire the U.S. subsidiary of Germany's Aixtron (Aixtron) for €670 million. In December 2016, CFIUS advised both parties to withdraw the application and abandon the entire transaction, and the acquisition of Aixtron by Fujian Hongchu ultimately failed.

In 2017, Canyon Bridge Capital Partners, a private equity firm backed by China Venture Capital Fund Corporation Limited, attempted to acquire U.S. Lattice Semiconductor Corporation. However, the U.S. government is concerned about the potential risks associated with the acquisition, especially given the importance of the semiconductor industry to national security. CFIUS recommended blocking the acquisition, and President Trump ultimately issued an order prohibiting the acquisition under the Defense Production Act of 1950.

4. 2017 Singapore Broadcom offered to acquire Qualcomm for $130 billion, but the deal was reviewed by CFIUS. CFIUS was concerned that the deal could threaten U.S. national security because Qualcomm is a major chipmaker, and CFIUS was concerned that Broadcom could undermine Qualcomm's leadership in 5G technology, thereby affecting U.S. national security. Ultimately, President Trump, on the advice of CFIUS, banned the deal.

5. On March 6, 2020 Beijing Zhongchang Shiji Information Technology Co. announced its acquisition of StayNTouch, but the acquisition was reviewed by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). In September of the same year, Shiji (Hong Kong) completed the closing procedures for the sale of 100% of StayNTouch and submitted a certificate of completion of the divestment of StayNTouch to CFIUS.

6. In November 2017, Bytespring acquired Musical.ly for nearly $1 billion and integrated it into TikTok, the overseas version of ShakeYin. however, the acquisition was not approved by U.S. regulators, and as a result, in 2019, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) opened a national security investigation into Bytespring. During the investigation, CFIUS entered into negotiations with ByteTok on measures to avoid divesting Musical.ly assets. Eventually, Musical.ly was merged into TikTok, which is owned by ByteDance.

All of these cases were called off by an executive order issued by the President.

Seeing this, all of us Chinese entrepreneurs must have a chill down our backs, so what is the standard of CFIUS review? What is a control transaction? What is a non-control transaction? What investments are subject to mandatory review? We'll go into more detail in the next issue.